Chapter 2: The First Words

Language as a building block of consciousness

Previously: The Ghost and the Skeleton

To build a model of consciousness, we must start at the bottom of the “software stack.” For the human mind, this is language—the building block of narrative consciousness.

Before humans had an internal “Self” to debate with, we had a biological input/output system. We didn’t have conversations; we had triggers. To see how this original system worked, we have to strip away the luxury of “thinking” and get down to the raw mechanics of survival.

Imagine for a moment that you are a prehistoric human standing in the tall grass of the savannah 500,000 years ago. You are foraging for roots, head down, focused on the dirt. Behind you, a lion moves silently through the brush, ready to pounce.

Your companion, standing on the ridge, sees the lion. He needs to warn you. He immediately yells “RUN! RUN! RUN!”, and the sound instantly triggers action in you. It’s a reflex—you don’t have time to think.

If your companion instead tries modern, descriptive language, you’re dead. If he calls out, “I believe there is a large feline approaching from the east,” by the time your brain processes the syntax, identifies the subject, and evaluates the statement’s truth, the lion has already eaten you.

Survival does not require description; it requires a trigger.

The first proto-word was not a noun. It wasn’t “Apple” or “Mother.” The first proto-words humans spoke were likely imperatives: “Run!” or “Climb!” It was a way for one brain to reach across the air to induce action in another.

Think of these proto-words as remote triggers. Their original purpose was not to describe the world, but to manipulate it. They were closer to programming code than conversation—an input signal designed to produce immediate motor output.

Modern humans did not invent this hardware; we inherited it from our ancestor species. We can still see its skeletal remains in our primate cousins, the vervet monkeys.

Vervet monkeys possess what appear to be proto-words, but these function less like vocabulary and more like switchboard circuits. Researchers have shown that the monkeys have specific vocalizations for specific threats: one sound—the “bark”—for leopards, another “cough” for eagles.

Crucially, these proto-words are not observations; they are instructions. When researchers played a recording of the leopard bark from a hidden speaker, the monkeys immediately scrambled up the nearest tree. When the eagle call was played, they huddled into the bushes.

The monkey’s brain treats the sound as an input that triggers a reflex. A line of code executing a script:

Input: Bark -> Output: Climb tree Input: Cough -> Output: Hide

There is no deliberation, no internal debate, and no narrative self. The sound bypasses the interpretive mind entirely and hot-wires the motor cortex.

The Hardware of Action

Early humans took this biological alarm system and upgraded it. We can still see the ancient wiring in modern fMRI scans. For decades, linguists believed words were processed in a discrete “language center” that worked like a dictionary. Recent studies have disputed that view.

When a subject in an fMRI scanner hears specific action words, the brain doesn’t merely “process” them—it simulates them:

Lick lights up the motor cortex for the tongue.

Pick lights up the motor cortex for the fingers.

Kick lights up the motor cortex for the foot.

This phenomenon, known as somatotopic activation, reveals that understanding a word is not an abstract intellectual act; it is a physical simulation. The word is not a label—it is a ghost impulse sent directly to the muscles.

This system is built on top of an even older shortcut: the acoustic startle reflex. A sudden loud noise doesn’t travel to the cortex to be “thought about.” It shoots directly from ear to brainstem to spinal cord to muscles.

You flinch before you know why you flinched. The “command” (the noise) executes the code (the jump) before the user interface (the conscious self) has even refreshed the screen.

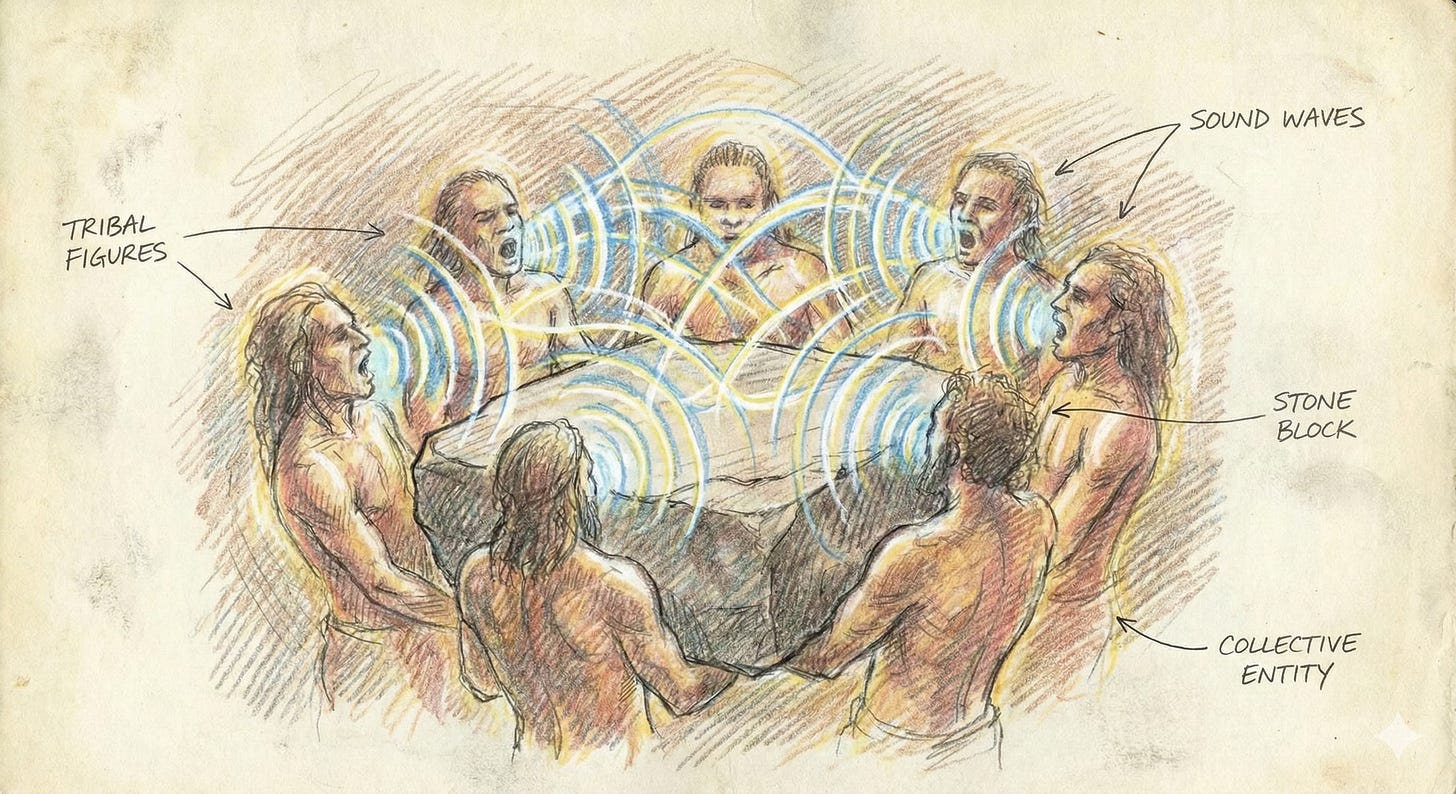

The Synchronization Engine

This hardware explains the reflex, but it doesn’t explain the rhythm. While a “Leopard Bark” is useful for reactive survival, it does not help a tribe build shelter or hunt mammoth. For that, humans had to solve the problem of synchronization.

Consider the problem of lifting a heavy stone. Six men can lift a weight that one man cannot, but only if they exert their force at the exact same moment. If they pull at random intervals, the stone effectively weighs more than their combined strength.

They need a way to align their time. And since a single shout fades too quickly to sustain effort, they need a loop.

Neurons work on thresholds. A single stimulus often isn’t enough to keep a major response going. This is called Temporal Summation. A single “spike” (a shout of “Run!”) might trigger a single twitch, but it fades before the muscle can fully engage for a long task.

But a rapid train of spikes (”Run! Run! Run!”) builds up the electrical potential in the receiving neuron, pushing it over the edge and holding it there. The repetition acts like a finger pressing down on a button, keeping the circuit alive and the action going.

Language likely expanded dramatically in this friction—the rhythmic grunts required to synchronize the muscles of the tribe.

Heave... Ho. Heave... Ho.

The rhythm serves as the clock cycle for the group. The grunt aligns the heartbeats and muscle contractions of six individuals into a single, functional unit.

This explains why, if you watch video footage of tribal hunters or warriors, you rarely hear a single, isolated utterance. Instead, you hear the same sound repeated over and over in a rhythmic chant.

In the 1963 documentary Dead Birds, there is extraordinary footage of the Dani people of the New Guinea Highlands engaging in deadly tribal warfare. As the lines of warriors approach each other, they do not rely on a commander barking out complex tactical orders. Instead, they coordinate their movements through a low, rhythmic, collective, almost hypnotic chant.

The chant acts as an external pacemaker for the tribe’s courage and aggression. It binds the group into a “Hive Mind.” If a warrior falls silent, he falls out of sync with the group’s rhythm, and his individual fear might take over. But as long as the chant holds, the group moves as one entity. The auditory loop keeps the “program” running.

The fossils of this prehistoric mind are still embedded in our neurology. Under stress, we can revert instantly to the rhythmic chant.

Watch a mother when her toddler runs toward a busy street. She doesn’t speak in a sentence; she yells, “Stop! Stop! Stop!” The repetition is not for emphasis; it is to hammer the auditory button until the child’s motor functions freeze.

Go to a basketball arena when the home team is losing possession. Thousands of distinct individuals suddenly dissolve into a single organism chanting: “Defense! Defense! Defense!” This is not a request. It is a primal synchronization hack.

Even drunk college students, on the verge of making a bad decision, will chant “Chug! Chug! Chug!” to override the hesitation of their peer. They are using the rhythm to bypass the listener’s judgment and trigger a motor action.

The Theology of Sound

In almost every ancient culture, words were viewed as having magical power. To the primitive mind, a word wasn’t a symbol or a representation; it was a force that physically moved the world. An incantation is simply code that executes on the hardware of reality.

We see this belief enshrined in the creation myths of almost every ancient civilization. To the prehistoric mind, the Universe was not built by hands; it was spoken by a voice.

In Ancient Egypt, the god Ptah created the world specifically with his Tongue, commanding matter into existence. In the Genesis account, God creates the world by issuing imperatives: “Let there be Light.” He speaks, and the output appears. He doesn’t snap his fingers or wave his hands. The New Testament is even more explicit: “In the beginning was the Word...”

In the Vedic texts of India, this is taken literally. The phrase Nada Brahma means “The World is Sound.” The universe is viewed as a vibration, a complex sentence being spoken by the creator. If the vibration stops, the world ends.

These aren’t just poetic metaphors; they can be read as memories of how the early mind experienced the world. For the prehistoric mind, Sound was the mechanism of Cause and Effect. If you wanted to move a rock, you chanted “Heave.” If you wanted to move the sun, you chanted a prayer. The mechanism was identical:

Input Sound -> Output Action

The Flaw

However, this mechanism had a fatal flaw: You need an active utterance to keep the action going.

A command to “Run” is only useful while the lion is chasing you. A chant to “Heave” only works while your hands are on the stone. You cannot chant “Plant the seeds in spring” to a tribe that is hungry in winter. The chant was a tool for the Now. It could coordinate immediate action, but it could not bridge the gap of time.

To build a civilization, the human mind needed a new invention. This “Action Language” was powerful, but it was ephemeral—it vanished the moment the sound waves stopped. You cannot build a future if your software only runs in the Now.

To solve this, the brain needed to upgrade its hardware. It needed to move from a system of Streaming to a system of Storage.

See the Introduction for more context on this project

Next: Recording and Replaying